by Thanasis Spanidis, commissioned by the Central Committee of the Communist Party

The question of the current character of Chinese society and the direction in which it is developing is the subject of controversial debate within the communist movement. Within our party, we have taken a clear and unified position on this question from the very beginning: Monopoly capitalist conditions prevail in China and China is embedded in a global imperialist system. This position is questioned and disputed by parts of the communist movement in Germany, but the discussions on this were often not well-founded. In order to close this gap and make our position clear, a comrade of the CP, Thanasis Spanidis, has explained the position in detail on behalf of the organization. We published the text at the end of 2023 and are now pleased to make it available in English translation. We have made every effort to correct problems with the machine translation. If we have made any errors, please let us know by email (info@kommunistischepartei.de)

Communist Party, April 2025

Content

1) Introduction: The Discussion About the Class Character of China

2) Clarification of Terms: Capitalism, Imperialism, Socialism

3) From Socialism to Capitalism: China in the Second Half of the 20th Century

a. Problems and Mistakes During the Revolutionary Period of the People’s Republic

b. The Break: 1978 and After

c. On the Classification and Assessment of the Counterrevolution in China

4) China’s Social System

a. State and Private Capital in Chinese Capitalism

b. Labor Becomes a Commodity: The Chinese Working Class

c. State, Party, and Bourgeoisie in China

d. Using Marx Quotes Against Marxism: The Ideology of the CCP

e. Interim Conclusion

5) China in the Imperialist World System: Crises, Capital Export, Risk of War

a. Crisis Developments in Chinese Capitalism

b. Chinese Capital Export

c. Consequences of Chinese Capital Exports for the Working People in the Recipient Countries

d. Military activities and interstate conflicts

e. Is there a Chinese Imperialism?

6) Conclusion: The Correct Position of Communists on China

1) Introduction: The Discussion About the Class Character of China

Is China a socialist state or, at the very least, a state that continues to work toward creating a socialist or communist society? Or is it already a capitalist society, where the bourgeoisie holds power?

This question divides the communist world movement like few others. And this division is not about being right or sectarianism. On the contrary—such a division on this question is inevitable and correct. For it concerns far more than just assessing the social conditions in a distant country—it concerns the principles of Marxism: the question of what is meant by capitalism, and, above all, what socialism actually is. It is about whether imperialism can still be grasped through the terms of Lenin’s theory of imperialism and thus understood as a developmental stage of capitalism and a global system encompassing all countries—or perhaps instead as an exclusive club of a handful of Western states that are classified as imperialist primarily due to their foreign policies. Finally, it is about whether, in the intensifying global political conflicts between China and the USA, an internationalist position is taken that defends the interests of the working class against both poles of the imperialist system, or whether, instead, the workers’ movement aligns itself with the pole of this world system led by China. The evaluation of China is, therefore, closely intertwined with the strategic questions confronting the communist world movement. The different and indeed opposing answers to this question from communist parties worldwide greatly influence the direction these parties take at the crossroads where the communist world movement finds itself today.

A significant part of the communist world movement believes that the People’s Republic of China remains a socialist country or a country taking steps toward socialist development. In Germany, this position is particularly vehemently represented by the German Communist Party (Deutsche Kommunistische Partei, DKP), which solidified this stance in a far-reaching resolution during its 25th party congress in 2023: „The DKP welcomes the successes of economic reforms and the increased global economic importance of the People’s Republic of China. This opens an alternative to the imperialist economic order. The Communist Party of China aims to develop the People’s Republic into a modern socialist state. There are capitalists in the country, but they do not hold political power. The state controls central sectors of the economy. This is the prerequisite for China’s development from an initial stage of socialism into a modern socialist country.“ Furthermore, „The DKP sees the improvements brought about for many countries through cooperation with socialist China and how these improve the conditions for the workers’ struggles.“ China’s foreign policy is fundamentally different from that of imperialist countries, which the DKP does not classify China as part of: „In this situation, the People’s Republic of China pursues a foreign policy aimed at maintaining peace and economic development. This policy of peaceful coexistence is a form of international class struggle that includes cooperation between countries with different social systems, without, however, abandoning ideological confrontation and the fight against imperialism.“1

A critique of this resolution by the DKP has already been provided in another text.2 Here, it will be demonstrated in more detail that the DKP and similar parties are fundamentally mistaken in these assessments.

One problem in debating this position is that claims about „socialism“ in China are often loudly proclaimed but rarely seriously argued or substantiated. On the contrary, their representatives often rely on platitudes and phrases. A scientific analysis of the class relations in China, the driving laws of the Chinese economy, and the class character of the Chinese state and the ruling „Communist“ Party is seldom carried out. One gets the impression that the supporters of the „socialism-in-China“ thesis prefer to express a declaration of faith rather than conduct a scientific analysis, especially as the debate is often highly emotionalized, and any dissenting position (especially any Marxist analysis that calls out capitalism in China by name) is sharply attacked.

When attempts are made to substantiate this position, the following arguments are typically presented:

- A centralized planned economy is not yet possible or practical in China due to the insufficient development of productive forces.

- Nevertheless, the pillars of a socialist economy in China remain intact, referencing the significant role of state enterprises in the Chinese economy and the continued state ownership of land.

- State power remains in the hands of the working class because the Communist Party of China governs the country.

- Therefore, China’s „reform and opening-up policy“ is not a policy aimed at establishing capitalist conditions but a necessary compromise on the path toward a developed socialist society, comparable to the New Economic Policy in Soviet Russia or the early Soviet Union.

- The socialist character of China is also evident in its international policy, which, unlike that of the USA, is not directed at war and subjugation of other countries but at peaceful coexistence, equality, and development.

These arguments rely on the official pronouncements of the Chinese party leadership. Historically, they can be traced back to Deng Xiaoping, under whose leadership and justifications the process of „reform and opening-up“, as it is called in China, began. Therefore, this stance is often referred to as „Dengism.“

Interestingly, some capitalists arrive at completely different conclusions. For example, Shan Weijian, a former World Bank and JP Morgan employee and CEO of a private equity firm in Hong Kong valued at $40 billion, said about Americans: „They don’t know how capitalist China is. China’s rapid economic growth is the result of its embrace of a market economy and private enterprise. China is one of the most open markets in the world: it is the largest trading nation and also the largest recipient of foreign direct investment, surpassing the United States in 2020.“ 3How is it possible that an internationally connected capitalist is as satisfied with the economic order of today’s China as certain groups in Western countries that regard themselves as communists? Unless, by some miracle, capitalists and the working class in China have learned to reconcile their opposing interests, we must assume that one of the two sides holds a significantly flawed view of the nature of China’s economic system.

The communist movement, based on Marxism-Leninism, is currently weak in addressing the China question, even though there are various analyses of China that provide important insights.4 However, critiques of Chinese capitalism often come from Maoist and Trotskyist perspectives, which tend not to delve into detail and instead rely on their respective terminologies and concepts (e.g., „bureaucracy“, „Stalinism“ for Trotskyists, and „social imperialism“ for Maoists). These terms often hinder a proper understanding of Chinese capitalism.

This text aims to provide a detailed analysis of the current Chinese economic and social order. It will show that characterizing China as socialist is incorrect and that all arguments supporting this view are individually wrong. It will demonstrate that capitalist laws dominate in China, making it a capitalist country where monopoly and finance capital prevail. It will also show that the Chinese state and the „Communist“ Party of China have a bourgeois class character and that China’s international relations are determined by the capitalist nature of its economy. We will see that these relations are essentially based on the exploitation of human labor power and that China seeks to promote a redivision of the world in favor of its monopolies. China is acting not only as a player within the imperialist world system but increasingly as one of the leading powers of global capitalism.

One must harbor no illusions: For some, the conclusions of this article will be unacceptable, leading them to simply ignore the facts and arguments presented here. The correct argument does not prevail merely because it is written somewhere. However, one can hope that the analysis provided here will help consistent Marxist forces combat Dengism and that there may still be enough openness among some influenced by Dengism to seriously examine the arguments presented.

The analysis will first clarify what is understood under the terms capitalism, imperialism, and socialism from a Marxist perspective. The next chapter will address the historical development of the People’s Republic of China from socialism to capitalism. Following that, the focus will shift to China’s societal system: in subchapters, the respective roles and weights of private and state capital in the Chinese economy will be examined; the situation of the working class, their struggles, and the transformation of labor power into a commodity will be briefly discussed; the subchapter on state, party, and bourgeoisie will demonstrate that the bourgeoisie is the ruling class in China and – contrary to the unsubstantiated claims of the DKP – also holds political power; and finally, the programmatic and ideological framework of the Communist Party of China will be presented, along with the question of what strategic goals the party pursues. The final chapter will address China’s position within the imperialist world system, the international role of Chinese capital and capital exports, the effects on the working population in the target countries of this capital export, and the inter-imperialist conflicts arising from China’s rise. A conclusion will be drawn about what constitutes a correct communist position on today’s China.

2) Clarification of Terms: Capitalism, Imperialism, Socialism

The question of the class character of the Chinese state and the Communist Party of China, as well as the characterization of China’s economy, presupposes certain terms whose meanings must first be clarified. It involves the question of how to recognize whether a country has a capitalist or socialist character. And what does it mean when we speak of imperialism?

Capitalism

Karl Marx, in the three volumes of Das Kapital, uncovered the economic laws that determine the development of the capitalist mode of production. He shows how, from the form of the commodity, which possesses both a use value and an exchange value, all capitalist relations necessarily develop. The value of commodities, whose quantitative amount is determined by the socially necessary labor time required for their production, ultimately determines the exchange relations between commodities. Marx calls this the „law of value.“ The law of value governs, in the capitalist mode of production, not only price movements but also the distribution of social labor across different goods and economic sectors and the incomes of the various social classes.

The capitalist relations of production are based on the private ownership of the means of production, which are concentrated in the hands of a social minority that Marx describes as the bourgeoisie or capitalist class. Opposing them is the working class, which increasingly becomes the social majority as the intermediary strata (particularly small farmers and the urban petite bourgeoisie) shrink. The working class has no significant private ownership of means of production and is forced to sell its labor power to the capitalists. Through the exploitation of labor power, not only is the invested capital reproduced, but surplus value is also created. Because capitalists are in constant competition with one another, they cannot fully consume the surplus value themselves; they must reinvest a significant portion in improved production methods and techniques to gain an advantage over their competitors. This leads to the accumulation of capital – and any capitalist enterprise that fails to accumulate capital is doomed to quick extinction. The appropriation and accumulation of surplus value is the sole and overarching goal of capitalists, which determines their success or failure in capitalist competition. The accumulation of capital knows no limits, whether in terms of the amount of accumulated capital, time, or space.

Capitalist relations of production can thus be summarized as follows: First, they consist of two opposing classes, one of which owns the means of production while the other lacks ownership and is compelled to sell its labor power to the capitalist class. Second, they involve competition among workers and capitalists alike because all commodities (including labor power) are traded in a market. Third, capitalists necessarily orient all their actions toward the unlimited accumulation of capital.

Commodity production and the capitalist mode of production are not immediately identical; that is, capitalist production entails more than just the production of commodities and their distribution according to the law of value. However, there is a close logical and historical connection between the two, as Marx makes clear. For Marx, the division of society into the working class and the bourgeoisie becomes „inevitable as soon as labor power is freely sold as a commodity by the worker himself. But only from then on does commodity production generalize and become the typical form of production; only then is every product produced from the outset for sale, and all produced wealth passes through circulation. Only where wage labor is its basis does commodity production impose itself on the entire society; but only there does it develop all its hidden potentials. To say that the intervention of wage labor falsifies commodity production means to say that commodity production, to remain uncorrupted, must not develop. To the extent that it progresses according to its own inherent laws to capitalist production, to that extent do the property laws of commodity production turn into the laws of capitalist appropriation.“5 Thus, for Marx, capitalist production necessarily arises from all commodity production and the workings of the law of value; capitalism is nothing other than the full unfolding of commodity production or the law of value. A „market socialism“, in which commodity production and distribution according to the law of value endure permanently – let alone private ownership of the means of production and exploitation – is inconceivable for Marx.

The capitalist social formation also includes the political rule of the bourgeoisie. Safeguarding capitalist property relations against any disregard for private property, organizing capital accumulation and favorable conditions for it, asserting dominance against revolutionary efforts, and constantly working to disorganize and politically weaken the exploited class all require the bourgeois state, which politically enforces the dominance of capitalists. Economic and political dominance are inseparably connected: On the one hand, the state, as the „ideal collective capitalist“, organizes the accumulation of capital, i.e., the enrichment of the capitalist class through the exploitation of the working class. On the other hand, the bourgeois state is also the site and instrument of direct dominance by the capitalists, who are interconnected with the state apparatuses through countless links and overlaps, enabling them to organize as the ruling class.

Socialism

What, then, is socialism? In Marxism, a socialist society is typically understood as a society in the initial, still immature stage of the development of communist production relations. Marx emphasizes that in such a society, various remnants and influences of the preceding capitalist mode of production persist: „What we are dealing with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but rather, as it has just emerged from capitalist society and is thus in every respect – economically, morally, and intellectually – still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges.“6 However, the decisive point is that the capitalist property and production relations have been overcome, existing at most on a small scale, while the new (socialist-communist) production relations already predominantly govern economic development.

Socialist-communist production relations are based on the social ownership of the means of production. This implies that production of use values can no longer be regulated (as in capitalism) through a market, i.e., supply and demand, nor is it driven by profit; instead, individual production units are subjected to an overarching societal plan. A central authority must determine the needs of society in advance and develop a plan that allocates raw materials, intermediate products, and labor across various economic sectors and enterprises to achieve the desired production result as efficiently as possible. The fundamental law of the socialist-communist mode of production is, accordingly, the planned development of productive forces to increasingly meet the needs of the population. Marx expresses it this way: „Economy of time, along with the planned distribution of labor time across the various branches of production, remains the first economic law on the basis of communal production.“7 Marx emphasizes the planned distribution of labor time under socialism – while labor time remains the measure in which products are related to one another, this is no longer done unconsciously and retrospectively through the market but rather in advance by central planning authorities. The notion of a „market socialism“, in which socialism is permanently compatible with the continued existence of commodity exchange and the law of value, fundamentally contradicts Marx’s understanding of socialism.

In a socialist society, remnants of capitalist production relations may exist in an early stage of development; however, these can no longer play a determining role (otherwise, the society as a whole would be capitalist, not socialist). It must also be the goal of the ruling working class to increasingly push back these elements: „This socialism is the declaration of the permanence of the revolution, the class dictatorship of the proletariat as a necessary passage to the abolition of class distinctions altogether, to the abolition of all the production relations on which they rest, to the abolition of all the social relations corresponding to these production relations, and to the revolutionizing of all the ideas arising from these social relations.“8

Just as capitalism implies the political dominance of the bourgeoisie, socialism represents the dominance of the working class, or, in the words of Marx and Engels, the dictatorship of the proletariat. This means that in a socialist state, the working class, through its own organs of power, enforces and defends social ownership of the means of production, and the communist party is tasked with advancing the planned development of communist production relations.

Imperialism

Unlike bourgeois understandings of imperialism, which view politics and economics as separate realms, Marxism-Leninism defines imperialism as encompassing both politics and economics, recognizing economic laws as the fundamental driving force of social development. Lenin writes about the economic basis of imperialism: „If a concise definition of imperialism is required, one must say that imperialism is the monopolistic stage of capitalism.“9 In Lenin’s understanding, imperialism signifies the dominance of monopoly capital. It corresponds to a stage of capitalist development that emerged at the end of the 19th century—initially in a few highly developed capitalist countries and subsequently spreading to almost the entire world.10 Today, imperialist conditions exist globally. While during Lenin’s time, only a relatively small number of imperialist states competed for the redivision of the world, monopoly capital as the economic basis of imperialism now exists in most countries, including many former colonies and semi-colonies. The colonial system that dominated much of the world’s surface at the time has largely disappeared.

From a Marxist perspective, imperialism today is not a characteristic of only a few countries but rather a highly hierarchical global system under the dominance of monopolistic capital. Some readers may not share this understanding. However, even if imperialism is regarded as a characteristic of only very few states, the question arises as to whether China belongs to these countries—whether monopoly capital predominates in China and to what extent China is involved in international capital export.

What Does This Mean for the Analysis?

It means we must examine the extent to which the law of value and capital accumulation govern China’s economy, whether property relations are primarily shaped by private or social ownership, and what role central planning plays. Furthermore, we must analyze which class dominates the Chinese state—whether it reflects the interests of the proletariat or the bourgeoisie. For assessing China’s international role, it is necessary to investigate whether monopoly capital has emerged in China, whether Chinese capital is exported on a significant scale, and how China is integrated into the imperialist world system.

First, however, it makes sense to historically examine the transition to capitalism in China.

3) From Socialism to Capitalism: China in the Second Half of the 20th Century

The Chinese Revolution and the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 was without a doubt one of the most significant events of the 20th century – if before 1949 there were hardly any people living under more miserable conditions than the Chinese, the country now embarked on the path towards socialism. By the mid-1950s, industry was nationalized, and in the 1950s, the small-scale peasant economies were merged into communes; with the help of central planning, a large-scale program was initiated to industrialize the country, increase agricultural production, expand infrastructure, and build a healthcare system and education system for the entire population. In the following decades of socialist construction, life expectancy increased enormously, and hundreds of millions of Chinese experienced a noticeable improvement in their living conditions. While China had been one of the poorest and least developed countries in the world in 1949, by 1978, at the end of the revolutionary period of the People’s Republic of China, poverty and underdevelopment had not yet been overcome, but the lives of the masses had vastly improved, and they had become the subject of their country’s history. And this country had experienced a tremendous developmental leap over the past nearly three decades – in a society where the wealth created collectively benefited all, where there was no exploiting class and no exploited class, and no significant social differences.

a. Problems and Mistakes During the Revolutionary Period of the People’s Republic

While the great achievements of the Chinese Revolution are evident and must always be defended against distorting anti-communist propaganda, it should not be overlooked that many problematic developments, which contributed to the reintroduction of capitalism after 1978, had their origins in earlier decades. Even though a profound rupture in the relations of production and ownership took place after 1978 – the dissolution of the socialist planned economy and the transition to capitalist social relations – there are certain continuities in the policies of the CCP both before and after 1978, without which the transition to capitalism is difficult to explain. The leading figures of the counterrevolution, such as Deng Xiaoping, Hu Yaobang, and Zhao Ziyang, had, unlike the Soviet counterrevolutionary leaders Gorbachev, Yeltsin, Yakovlev, or Gaidar, fought in the revolution. Now they were pioneers of the dismantling of socialism. How was such a thing possible? This immediately raises the question: Did the CCP already previously adopt positions that later facilitated a departure from the socialist path?

The problematic, revisionist tendencies of the CCP before 1978 can only be briefly examined here and will be dealt with in more detail in another text. A brief look into the history of the revolution is necessary: The CCP had to fight its way to socialism both against the domestic counterrevolution in the form of the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-Shek and against Japanese occupation. China was territorially divided among various warlords, and so it first had to be unified and liberated from foreign invaders. At the same time, capitalist relations had only just begun to emerge in the cities, while in the countryside, the peasants lived in dependence on large landowners. The tasks facing the CCP were therefore manifold: national and anti-colonial liberation, overcoming pre-capitalist relations of oppression and large landownership, and, of course, building a socialist society. In the theory of the CCP, and especially in the thinking of Mao Tse-tung, the national rebirth of China and socialism were interconnected and mutually reinforcing. This was not wrong in itself – of course, it was correct that the CCP led the struggle for China’s liberation from its semi-colonial status. However, what was problematic from the beginning was the idea that a part of the bourgeoisie could participate in the revolution – because, according to Mao, the contradiction between the working class and the national bourgeoisie in China, if handled correctly, was not an antagonistic contradiction, but rather a “contradiction among the people.”11 Contained within this was an understanding of socialism as a joint struggle of the entire Chinese people (from which only the “compradors”, who were linked to foreign imperialism, were excluded) against foreign powers.

Mao analyzed social and political conflicts using the terminology of “primary and secondary contradictions”, which he developed himself. According to this, in a specific phase of development, one particular contradiction is always the principal contradiction, by which Mao simply meant the predominant, most important conflict, while the others were secondary contradictions. The principal contradiction was thus determined relatively arbitrarily by whichever political struggle happened to be dominant in the country at the time. As a category for analyzing the societal foundation, this concept was not as suitable as the term fundamental contradiction used by Engels, which refers to the basic contradiction of society from which all other contradictions develop. However, Mao went even further and emphasized that principal and secondary contradictions frequently switched places, so that a particular conflict that had just been the principal contradiction could suddenly become a secondary contradiction, and vice versa.12 Thus, it was possible that during the fight against Japanese occupation, the CCP defined the struggle of the Chinese nation against Japan as the “principal contradiction”13, in 1952 the contradiction between the working class and the bourgeoisie14, and from 1956 the contradiction “between the needs of the people for rapid economic and cultural development and the inability of our economy and culture to meet these needs.”15 Ultimately, by seeing the most important task of socialism as the development of the productive forces rather than the development of new production relations, an idea was already laid out that Deng Xiaoping would later adopt and make the centerpiece of his worldview: for Deng, as we will see later, socialism was equated with economic growth.

The “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution”, whose mastermind and leading figure was Mao, can be seen as an attempt to correct this one-sided prioritization of the development of productive forces. However, the method chosen for this – the mobilization of the masses against the party apparatus, the development of an absurd personality cult, the largely indiscriminate rejection of the entire previous culture, and the paralysis of the education system – weakened socialism instead of strengthening it. It did not lead to a correction of the opportunistic tendencies in the party but rather enabled them, after the end of the Cultural Revolution and Mao’s death, to achieve a breakthrough. However, this must be discussed in more detail elsewhere.

Another factor that facilitated both the rise of pro-capitalist forces and the growth of the capitalist economy was the extremely problematic foreign policy of the PRC during the Mao era. After the rupture in relations with the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, the Soviet Union was, first of all, discredited as a model of socialist development within the CCP. While Mao and the party leadership argued that the Soviet Union had supposedly reintroduced capitalism after Stalin’s death – a completely anti-Marxist claim, which was never seriously substantiated by the Chinese Communist Party – it paradoxically made it easier for the right-wing group around Deng Xiaoping later on to suppress Soviet experiences and the debates on socialist economic planning from the discourse and thus to present the use of the market as the only solution to economic problems.

At the same time, beginning around 1971, China moved significantly closer to the United States. The fact that the United States, as the leading power of capitalism, was now effectively China’s ally, while the Soviet Union, as the leading power of the socialist camp, was seen as the enemy, weakened the forces within the CCP that sought to maintain socialist relations of production. Moreover, this alignment opened the possibility of using the inflow of foreign capital to catch up technologically in key areas and to develop the fledgling Chinese capitalism relatively unbothered by the United States – which was initially preoccupied for another decade with the Soviet Union as its main adversary – and to benefit from growing trade with them.16

b. The Break: 1978 and After

After Mao’s death, the so-called “Gang of Four”, a group of leading figures of the Cultural Revolution, attempted for a short time to continue the Cultural Revolution’s program. However, within just a few weeks, they were overthrown, arrested, and sentenced to long prison terms. Even the new chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Hua Guofeng, only led the party for a short period. An assessment and evaluation of his tenure cannot be provided here, but in any case, he was ultimately ousted by the further right-leaning group around Deng Xiaoping in the party leadership, who criticized his policy of the “Two Whatevers”: according to this slogan, which had been propagated in several official media under Hua, it was declared that everything Mao had decided and everything he had instructed would be resolutely upheld and followed.

Under Deng’s new leadership, a definitive break occurred in the policies of the CCP, initiating the gradual dismantling and abolition of socialist relations and the transition to capitalism.

This process took place in several steps: At the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the CCP in December 1978, the process of the “reform and opening-up policy” began, and Deng Xiaoping established himself as the leading figure of the party, prevailing against Hua Guofeng. The first step was a rupture in social relations in the countryside: the people’s communes, in which the peasantry had previously been organized – large units the size of small towns, where detailed production planning took place, but where social services were also extensively collectivized – were dissolved into private households in 1978. By 1983, 98% of peasant households had been transitioned to the new system, and apart from a few isolated “islands”, the commune system was abolished.17 On paper, the land remained state property, but in practice, it was treated as private property. By the late 1980s, tenants already had full rights to lease, sell, or pass on land through inheritance.18

In the following year, 1979, local “experiments” with capitalism were conducted as a second step. In selected cities, private enterprises and cooperatives were allowed to operate relatively outside the central plan.19 These local experiments were generalized and expanded in the following years – a pattern the Chinese government would frequently apply from then on.

At the same time as private capital and cooperatives were expanded, and thus the scope and binding nature of the central plans were further weakened, the workforce was gradually turned into a commodity as a third step, and a labor market was created. Starting in 1983, state enterprises began employing contract workers for limited periods without social protection, which represented a departure from the previous form of employment. By 1987, approximately 8% of industrial workers were such massively disadvantaged contract workers. After private wage labor had existed in China only to a very limited extent, its scope began to increase again.20 For the living standards of the urban working class, this initially meant significant setbacks: according to official data, in 1987, 20% of urban families experienced a decline in real income, while the Chinese trade union federation reported that, on average, real income in the cities fell by 21% in that year alone.21

A key role in the transition to capitalism was played by so-called township and village enterprises (TVEs) – formally collective enterprises that, in fact, were often disguised private companies. These enterprises expanded massively in villages and small towns in the 1980s and, through their “collective” legal status, circumvented restrictions that still applied to private companies. Their profitability often relied on offering workers significantly lower wages and social protections compared to state-owned enterprises.22However, the boom of the TVEs did not last long. By the 1990s, the managers of these enterprises, who were already acting as their de facto owners, tended to systematically plunder the firms by siphoning off capital for their own enrichment. Since they rightly assumed that they would soon be able to purchase these enterprises anyway, they deliberately reduced their value through such asset transfers to ensure they would later pay a lower price for them. Starting in 1996, the TVEs were formally privatized on a large scale by local authorities in villages and small towns, generally transferring ownership to their former managers.23

Through the privatization of TVEs, as well as other enterprises, a new capitalist class emerged in China, after the bourgeoisie had ceased to exist as a class between 1956 and the late 1970s. Party officials and directors of state-owned enterprises also exploited their positions of power to appropriate parts of the enterprises‘ capital or to divert state subsidies for their firms for private purposes (such as travel expenses or private educational fees for their children). State property was sold – either illegally with the tacit approval or active encouragement of authorities or legally at undervalued prices.24 The transfer of state-owned property to the new bourgeoisie, i.e., the expropriation of the Chinese working class, took on enormous proportions: according to one estimate, approximately 5 trillion (!) US dollars worth of state and collective property was transferred to individuals with good connections to the government during the privatization process. By 2006, as a result of this massive expropriation program, there were 3,200 individuals with assets worth over 15 million US dollars each – and approximately 90% of these were high-ranking party and state officials or their family members, whose combined wealth in 2006 was equivalent to the country’s entire economic output at the time (about 3 trillion US dollars).25 Thus, the process of “reform and opening up” represented an unprecedented joint plundering by leading economic, state, and party officials, through which they transformed themselves into a new ruling class, a new Chinese bourgeoisie. This new bourgeoisie was already closely intertwined with the state apparatus through its formation process and occupied key positions within it.

1992 marked another milestone: the year began in January and February with Deng Xiaoping’s famous tour of the southern Chinese provinces. During his trip, Deng held discussions with many officials, urging them to accelerate the capitalist “reforms” and to remove individuals from leadership positions if they were not sufficiently committed to these reforms. In October, at the 14th Party Congress of the CCP, the goal of a “socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics” was formulated. Concretely, this meant abandoning the role of the state sector as the central anchor of the economy, which was already heavily infiltrated by capitalist elements. Many state-owned enterprises were now privatized and converted into joint-stock companies. By 1997, 107 of the 500 largest industrial enterprises had become joint-stock companies, meaning they were at least partially under private ownership. The government’s strategy was now summarized as “Grasp the big, let go of the small”, meaning that the largest 1,000 enterprises would remain under state ownership while the rest would be sold to private capitalists.26

After Deng’s southern tour, the significance of foreign investment in Chinese capitalism grew rapidly. Up until then, investments had mainly come from overseas Chinese capitalists in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao, and other East Asian countries. These networks of overseas Chinese capitalists with mainland China facilitated the inflow of capital and essentially paved the way for other capitalists, who also began to invest in China in the 1990s. The Chinese government actively promoted this influx of capital, officially designating Taiwanese capitalists as “patriotic ethnic Chinese” and “special domestic capital” as early as the late 1980s. This classification gave them far better access to the Chinese market than other foreign investors enjoyed.27

As a result of all these interconnected transformations, the transition of Chinese society and economy from socialism to monopolistic capitalism was carried out and completed in the 1980s and 1990s. This process must equally be characterized as a counterrevolution, similar to the dismantling of the Soviet Union and the Soviet socialist planned economy at the end of the 1980s to 1991.

c. On the Classification and Assessment of the Counterrevolution in China

The transition to capitalism within the CCP was by no means uncontested; rather, the pro-capitalist elements in the party had to assert themselves through significant struggles. Criticism of the, at times, highly voluntaristic and counterproductive economic policies of the Mao era (particularly during the “Great Leap Forward”, but to a lesser extent also during the “Cultural Revolution”) served as justification for the gradual departure from the planned economy. It was as if the “Great Leap Forward” were an inherent feature of socialism rather than a specific historical decision.

In the influential textbook by the economist Xue Muqiao from the 1980s, for example, it states: “To better implement these (the state-determined development priorities, editor’s note), we previously relied on bureaucratic measures instead of making use of the law of value. In particular, agriculture was regulated in a command-economy manner.”28 And: “We should therefore, under normal economic conditions, that is, when social purchasing power essentially corresponds to the supply of goods, make more use of the law of value than before. Instead of rationing goods, the balance between supply and demand should be achieved through price movements. (…) Only the prices of a few vital goods should be uniformly set by the state.”29

With “bureaucratic measures”, economists like Xue obviously simply meant that the economy was socialist, that is, centrally planned. The planning and control of the economy appeared to them as “unnatural”, while market regulation, or the law of value, was seen as the “natural” and appropriate form for any economy. Increasingly dominant in China were such intellectuals who still invoked Marxism in superficial phrases but no longer had anything substantive to do with it.

Today, the main political justification of the CCP, or its supporters abroad, for China’s gradual departure from the planned economy starting in 1978 is the argument that this transition extraordinarily accelerated China’s economic growth. Even nearly three decades after the revolution, China was allegedly so backward that the CCP simply had no choice but to act “pragmatically” and introduce elements of capitalism – supposedly temporarily – in order to catch up with the leading capitalist states. This argument is based on a very far-reaching and highly questionable assumption: namely, the belief that a capitalist system is fundamentally superior to a socialist, that is, a planned economic system, and that it produces higher growth rates. This assumption is not only theoretically dubious30; it also completely ignores the fact that economic growth is a class-neutral concept, which says little about whether this growth actually increases the well-being of the broad masses or whether it is perhaps paid for by the working class through low wages, lack of workplace protections, and long working hours.

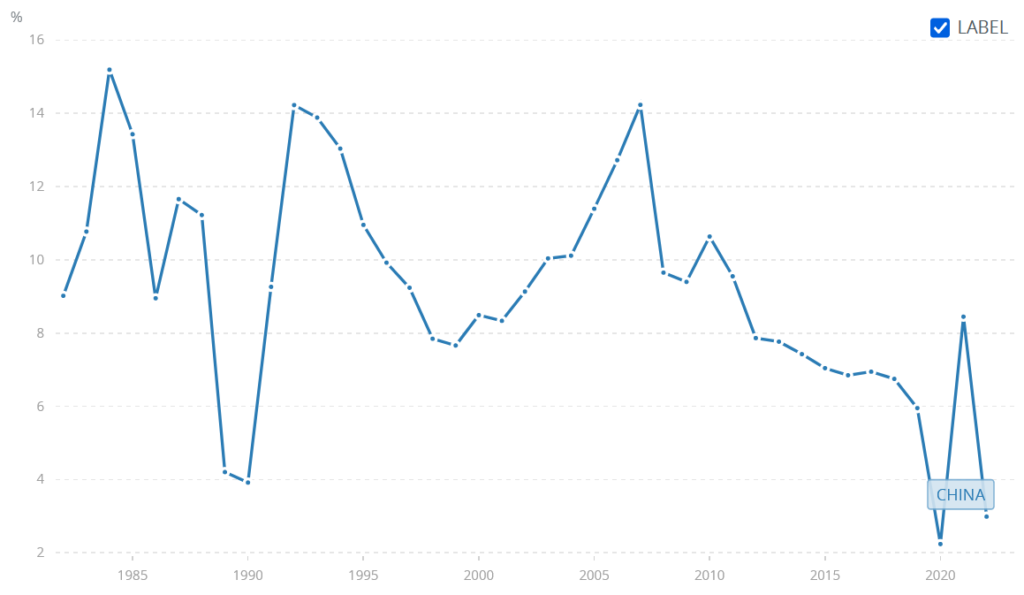

But let us set all of this aside for now and consider on its own the claim that the introduction of the „market economy“, that is, capitalism, led to significantly higher growth rates in China’s economy. The British economist Angus Maddison provides data on China’s GDP from 1952 to 2003, from which the annual economic growth can be calculated. According to this data, economic growth in China between 1953 and 1978, that is, up until the start of the „reform and opening-up“ policies, averaged 4.6% annually. Between 1979 and 2003, however, it was 7.9%. At first glance, this confirms the verdict that while economic growth under Mao was indeed high, it was still significantly lower than after the beginning of the „reforms.“ Was it really capitalism, then, that freed China from the „socialist administration of poverty“, as anti-communist authors claim?

The problem with this is that such a superficial comparison overlooks something crucial: during its socialist period, China was struck by two severe economic downturns – during the „Great Leap Forward“ from 1958 to 1962 and during the „Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution“ from 1966 to 1976. These downturns were obviously not the result of central planning but rather of political decisions which, in both cases (but significantly more during the Great Leap Forward), created economic chaos. What picture emerges when the years of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution are removed from the calculation? Then, the average annual growth rate in the period from 1952 to 1978 was actually 8.2%, and thus even slightly higher than in the period from 1979 to 2003. Conversely, this high growth could also be partially attributed to the recovery after the severe downturns of the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution, which again would relativize the better performance of the planned economy – all of this highlights how limited the explanatory power of such comparisons is.

Therefore, a more concrete analysis of the drivers of growth is required. A particularly significant fact, which also contradicts the bourgeois narrative of a more efficient capitalism, is that during the final years of the socialist developmental phase, numerous large projects in industry and infrastructure were initiated, whose positive impact on economic growth only became evident in later years, that is, in the late 1970s and 1980s.31 For example, during the Cultural Revolution, many roads and railway lines were built, large steel plants were opened, and especially in rural areas, infrastructure was greatly expanded: “One of the reasons for the good results in grain production in the post-Mao era is that the enormous amount of labor invested in irrigation projects, particularly during the Cultural Revolution, paid off in the years immediately after Mao’s death. From 1966 to 1977, 56,000 medium and small power stations were built, connecting 80% of the communes and 50% of the production brigades to the power grid. Irrigation powered by electric pumps reached a capacity of 65 million horsepower. More than 20,000 electrically driven wells were built, which could irrigate more than 700 million mu of land (one mu corresponds to approximately 0.0667 hectares).32 Compared to 1965, the irrigated area in China increased by 51%, electricity consumption in agriculture by 470%, electrically driven wells by 935.89%, the electrically irrigated area by 355.58%, the available tractors by 5.7 times, and the hand tractors by 65 times.”33 Additionally, there were large-scale irrigation projects such as the Haihe and Liaohe projects, which involved thousands of kilometers of dikes, thousands of bridges and sluices, and tens of thousands of water reservoirs. All of these projects were not included in the GDP during their construction phase, which is why the GDP in the statistics appears lower than it actually was. At the same time, however, these investments contributed enormously to economic growth in the following years, so they distort the direct comparison of growth statistics in two ways.34

This is not to say that there were no economic problems at the end of the Mao era. Wages had stagnated for a long time, the growth of food production was moderate (though still higher than in most countries at a comparable level of development), and product quality often left much to be desired. On the other hand, industrial growth was very high, and unlike almost all other countries of the so-called “Third World”, China was free of foreign debt. The economic situation was by no means disastrous. Most importantly, it is completely implausible to claim that the existing problems could not have been solved within a socialist economy. Rather, a look at the facts demonstrates the impressive achievements of the socialist planned economy in China. The decision to dismantle socialism was not the inevitable consequence of an overwhelming crisis but rather the result of the political enforcement of a specific right-opportunistic and pro-capitalist line within the leadership of the CCP.

As a result of the counterrevolutionary processes, a qualitatively different economic and social system emerged in China, which increasingly had little in common with the socialist system of the Mao era. This system will now be analyzed in the following section.

4) China’s Social System

The following section is divided into four subchapters, each dealing with the following aspects of the Chinese social system: a) the economic system and the role of private and state capital as well as economic planning; b) the transformation of labor power into a commodity, that is, the creation of an exploited working class through capitalism, the condition of this class, and its struggles; c) the bourgeoisie in China and the instruments of its rule, especially its connection to the state and the “communist” party; and d) finally, the ideology and program of the CCP, the proclaimed goals of the “socialism with Chinese characteristics” and the society aimed for with this concept. This will also involve refuting a widespread myth, namely that the CCP introduced capitalism only temporarily.

a. State and Private Capital in Chinese Capitalism

The dismantling of the socialist planned economy starting in 1979 naturally signified a profound upheaval in the functioning of the Chinese economy. The state-owned enterprises, which represented the most important units of the economy during the socialist phase of Chinese history, were largely privatized in the 1990s and early 2000s. At the same time, the widespread assumption that, over time, all state-owned enterprises would gradually be sold off and China would become an economy modeled after the West has not been fulfilled. State influence on the economy remains high, leading both some liberals and certain leftists to the mistaken conclusion that China is still not a “real” capitalism.

We will therefore now examine the forms of ownership in Chinese capitalism and the economic role of the state in the Chinese economy as well as the role of the private and state sectors. We will see that the distinction between state and private sectors is by no means synonymous with the opposition between socialist and capitalist economies, and that both China’s private and state enterprises have a capitalist character.

To begin with, it is helpful to get a rough idea of the size of the state sector in the Chinese economy. However, this question is not so easy to answer, as there are no official statistics available. Generally speaking, the state is heavily concentrated at the top of the rankings of enterprises: while there are millions of small, medium, and large privately-owned firms and relatively few state-owned enterprises, most of the largest corporations remain state-owned.

Today, the largest monopolies in China, which simultaneously rank among the largest in the world, can be divided into three broad groups in terms of their ownership structure: first, there are state-owned enterprises, especially in strategic industries such as the oil corporations Sinopec and CNPC, the energy conglomerate SGCC, and the construction company CSCECL. The second group consists of effectively mixed publicly listed companies that are still classified as state enterprises because the state exercises controlling influence over them. These companies can be found, for example, in the financial sector, including the major banks ICBC, Agricultural Bank of China, and Bank of China, as well as the insurance giant Ping An Insurance. Finally, the third group includes a number of private companies among the largest monopolies, some of which have a state minority share. These predominantly private-capitalist companies are found in areas such as electronics and the Internet, including companies like Huawei, Lenovo, Tencent, and Alibaba.

However, focusing on the largest of the massive Chinese monopolies can be misleading because it fosters the illusion that state ownership remains dominant in China. This is by no means the case when one considers capital as a whole and not just the thin layer of the very largest monopolies.

Estimates from around the mid-2010s mostly agreed that state-owned enterprises in China accounted for approximately 40% of value creation and 20% of workforce employment.35 The most recent study on this question, which could be found, dates to 2019. According to this, two different estimation methods yielded a share of Chinese state-owned enterprises in China’s GDP of between 23% and 27.5% and a share of employment between 5% and 16%.36

These shares still sound relatively high and are indeed so compared to most other contemporary capitalist economies. However, as we will see, they can easily be misinterpreted: the fact that state-owned enterprises today presumably account for about 25% of value creation does not mean that 25% of value creation is state-owned – because in state-owned enterprises, the state is not the only shareholder and usually owns less than half of the shares. Conversely, this figure above all means that in supposedly “socialist” China, approximately 75% of total production and probably around 90% of employment takes place in non-state, that is, primarily private companies.37

How did such a development come about in a formerly socialist planned economy, where private capital ultimately managed to assume a clearly dominant role?

Privatization and Capitalist Restructuring of the State Economic Sector

The transition from an economy where social ownership of the means of production dominated to one where the means of production are predominantly in the hands of private capitalists occurred in China – unlike in the Soviet Union and most other formerly socialist countries – gradually, over a period of many years. The key stages of this process were as follows:

In the first phase of the so-called “reform and opening-up policy” from approximately 1978 to 1984, the focus of policy was on granting managers of state-owned enterprises greater autonomy in business decisions and partially separating enterprise budgets from the state budget. Enterprises were thus allowed to produce outside the binding state plan, and exporting enterprises were permitted to retain part of the foreign exchange they earned and spend it at their discretion. In this way, even in the early stages of capitalist restoration, the central planning of investments and the distribution of goods was severely undermined.38

In 1984, another decisive step was taken with the introduction of a system whereby managers of state-owned enterprises were given complete control over the management of their firms through their employment contracts. They were thereby obligated to pay a fixed amount of profits to the government and could keep the remainder. By 1988, 93% of all firms had already switched to this system. This had two main consequences:

First, managers were now only interested in short-term profits. Since they typically managed a firm for only three to five years, there was no longer any incentive to make long-term investments or even to maintain the stock of fixed investments. It was far more profitable to plunder state-owned enterprises as thoroughly as possible and enrich themselves. By the early 1990s, as a result, 40% of state-owned enterprises had been so depleted that they were recording losses.39 Second, this automatically created a class in China that had been abolished by the revolution: a capitalist class that gained significant control over still state-owned means of production and privately appropriated a large portion of surplus product in the form of profit. By the second half of the 1980s, the Chinese social order had thus entered a transitional phase – these were the years of the shift from socialism to capitalism.

The qualitative leap into capitalism was completed in the early 1990s. Following a series of influential speeches by Deng Xiaoping emphasizing the importance of the market for economic development and after the 14th Party Congress of the CCP enshrined the goal of the “socialist market economy”, the focus of the “reform and opening-up policy” shifted. Whereas previously the emphasis had been on changes to enterprise management, state ownership of the means of production now came directly under attack. The opening of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges enabled state-owned enterprises to go public and thus sell shares to private investors.40 Listing on the stock market meant that these enterprises were, from that point forward, subject to the imperative of distributing returns and were thus primarily oriented toward profitability criteria.

In 1978, when Deng Xiaoping assumed leadership of the CCP, 77% of industrial production was accounted for by state-owned enterprises, while the remaining 23% was attributed to collective enterprises, which, according to the law, belonged to the workers on site. This changed drastically in the 1980s and 1990s. By 1996, the share of state-owned enterprises had already fallen sharply to 33%, with the remainder divided among collective enterprises (36%), which by then mostly represented a disguised form of private enterprise, official private companies (19%), and foreign enterprises (12%).41 Between 1996 and 2006, the privatization of state-owned enterprises was further accelerated: their number was halved, and approximately 30-40 million workers were laid off. However, privatization also affected those enterprises that continued to be listed in statistics as state-owned. This is because these companies were now granted the right to sell shares of the enterprise to investors.42

In the 2000s, the focus shifted to the reform of the remaining large state-owned enterprises. The smaller and strategically less important of these enterprises were transferred to local and regional governments. Large enterprises deemed strategically important remained in the hands of the central state, which in 2003 created the SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) for this purpose. The SASAC reports to the State Council, that is, the government, and acts as the central state shareholder in state-owned enterprises. At the same time, it is responsible for overseeing a selected group of large state-owned enterprises. When the SASAC was founded, this included 189 „central state-owned enterprises.“43

The privatization processes in the large state-owned enterprises no longer occur today at the same rapid pace as around 20 years ago, which indicates a policy shift by the Chinese leadership: unlike in the 1990s and early 2000s, the motto is no longer to sell off all state property to private investors as quickly as possible. Instead, both state and private ownership of the means of production are now recognized by the government and party leadership as legitimate components of the system.

In 2013, the CCP Central Committee decided to redefine or elevate the role of the market in the conception of the Chinese economic system. Until then, official statements had mentioned that the market should play a “basic”role in the allocation of resources to branches of the national economy. Since then, it has been stated that the market plays the “decisive” role in the Chinese economy.44

In the same year, the National People’s Congress, that is, China’s parliament, approved a new wave of state-owned enterprise reforms: “For competitive sectors, the instruction was to ‘steadily promote the mixed ownership of state-owned enterprises and ensure that both state and non-state capital participate in the operations of the respective state-owned enterprises,’ while for strategic sectors, ‘state-owned enterprises in the respective sectors should remain in state hands, while encouraging participation by non-state parties.’”45

In the following years, further major privatizations took place: for example, in 2017, the second-largest telecommunications company, China Unicom, sold 35% of its shares on the Shanghai Stock Exchange to a group of private and state investors. As a result, the state holding company, which until then held 63% of the shares in the company, fell to 37%. This is particularly significant because the telecommunications sector had previously been considered a strategic sector under strict state control.46 A bourgeois study accordingly expressed its satisfaction: “It is a promising trend that more private capital is being allowed into strategic and pillar industries, as this introduces more competition and leverages the technical, management, and strategy know-how of private enterprises.”47

At this point, it should also be mentioned that countertrends existed: the state simultaneously bought into private companies or even took them over completely, primarily in the form of state bailout packages for bankrupt firms.48 Such examples are often cited to argue that the Chinese state is strengthening its control over the economy – either by economic liberals, who paint the “specter” of a return to China’s planned economy, or by Dengists, who use this to demonstrate a socialist orientation and therefore evaluate these measures positively. As has already been shown, however, the overall trend clearly continues in the direction of strengthening the private sector relative to the state sector, and not in the opposite direction.

With the new directive of 2013, the CCP Central Committee and the State Council also implemented a division of state-owned enterprises into “public” and “commercial” categories. The “public” enterprises are those responsible for the provision of essential goods and in which the state intends to retain decisive influence. These enterprises are therefore to remain subject to political decisions, although they are also simultaneously directed toward cost reduction and profit maximization. The “commercial” category, on the other hand, is to be comprehensively exposed to market competition and focus primarily on generating profits.49

Another reform of the management of state-owned enterprises was adopted in 2014. This reform, in various forms, aimed to transform the state from a direct administrator of companies into a manager of securities for these companies, to give state-owned enterprises more freedom in appointing their leadership, and to advance the privatization or partial privatization of some state-owned enterprises by having the state sell part of its shares to private investors.50

In 2019, a new law on foreign direct investments made it easier for foreign capital to flow into the Chinese economy. Until then, foreign investors in many industries had been required to establish joint ventures with Chinese companies. This law exempted a range of additional industries from the regulation and thus opened them up for foreign investments.51

In July 2023, the CCP Central Committee, together with the government, published a key document on the expansion of the private sector. It stated: “To resolutely resist and immediately refute false statements and actions that undermine or weaken the fundamental socialist economic system, that negate or downplay the private economy;” “to support private economic actors in playing a greater role in international economic activities and organizations;” “to encourage various levels of government departments to consult outstanding entrepreneurs and utilize their role in the formulation and evaluation of policies, plans, and standards related to enterprises;” and “to prudently recommend outstanding private economic professionals as candidates for representatives of the People’s Congress at all levels and as members of the CPPCC52, with the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce playing a leading role as the main channel for the orderly political participation of private economic professionals.”53

In summary, the document includes:

- A clear commitment to expanding the role of the private sector in Chinese capitalism and a fight against still-existing viewpoints that seek to diminish this role.

- The strengthening of international economic diplomacy by Chinese capitalists with the aim of better global representation of the interests of Chinese monopolies.

- The increased direct involvement of capitalists in the drafting of laws and political measures.

- A guaranteed presence of capitalists in leading state organs.

We will examine some of these points more closely in the following chapters, but this statement already provides a preview of what to expect there.

The continued and deepened capitalist reforms since Xi Jinping assumed the presidency in 2013 also refute the myth, popular in some parts of the communist movement and propagated by certain bourgeois media, that China under Xi Jinping is once again turning towards a socialist orientation. But more on that later.

What Function Do State-Owned Enterprises Serve?

The continued importance of state-owned enterprises in a predominantly private economy indicates that state-owned enterprises in the Chinese economy perform three main functions:

First, they are meant to provide infrastructure and essential services that increase social and political stability, but most importantly, that can also be made available for the accumulation of private capital. Thus, private capitalism in China can rely, for example, on a well-developed transport and communications network as well as cheap energy, which represents a decisive advantage in international location competition.54

Second, state-owned enterprises are also tasked with accumulating capital themselves and being developed into internationally competitive monopoly corporations.

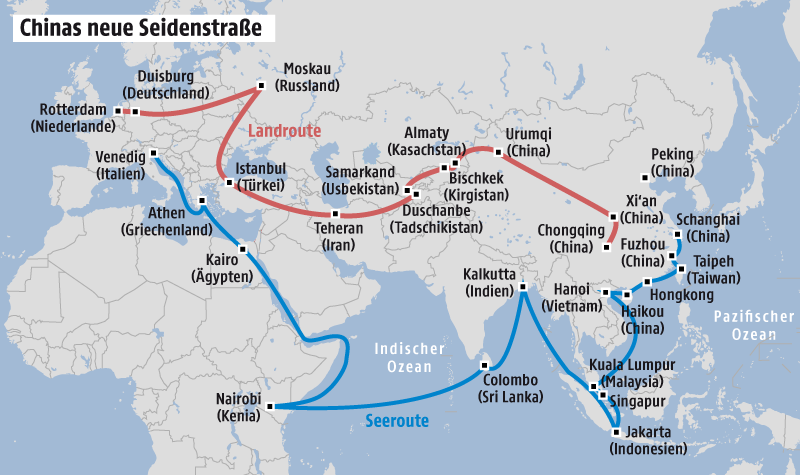

Third, and connected to the first two functions, state-owned enterprises are also supposed to expand markets internationally and ensure the supply of raw materials for the growing capitalist economy. For example, under the Belt and Road Initiative, loans from state banks, infrastructure projects (often carried out by Chinese state-owned enterprises), and resource extraction in other countries are closely interconnected.

All three functions are not unusual for capitalist countries. There are examples in almost all economies of states retaining certain enterprises because privatizing them can have harmful macroeconomic consequences. This particularly applies to infrastructure and communications companies (telecommunications, railways, water, and power supply), but also, for example, to the extraction of certain raw materials.

As for the second function, it is true that in most developed capitalist countries, privately owned monopolies hold a dominant position in the economy and in capital export. Nevertheless, the targeted development of “national champions”, that is, internationally competitive top corporations in (majority) state ownership or with massive state support, was for decades central to the economic strategies of other East Asian countries such as South Korea and Japan, but also France.

An example of how internationally leading monopoly corporations emerge under state guidance is the field of artificial intelligence. In the multi-stage “Plan for the Development of a New Generation of Artificial Intelligence” from 2017, the Chinese government stated: “By 2030, China’s AI theories, technologies, and applications should have reached a globally leading level, making China the world’s primary AI innovation center, achieving visible results regarding applications in the fields of intelligent economy and intelligent society, and laying an important foundation for a leading innovation-driven nation and economic power.” This is to be achieved through a systematic policy of technological development, the establishment of large internet corporations, and the acceleration of “the creation of globally leading AI enterprises and brands in advantageous areas such as unmanned aviation, speech recognition, pattern recognition (…) smart robots, smart cars, wearable equipment, virtual reality, etc.”55

To clarify the comparison with France: in the post-war period, the model of “planification”, that is, a planned capitalism, was created there, in which the central state guided economic development by providing targeted incentives for companies to strengthen the position of French capital in competition as part of a national economic development strategy. This included, in particular, the nationalization of many key industries and banks and the targeted development of so-called “national champions”, i.e., predominantly state-owned enterprises that were meant to achieve global competitiveness under the protective hand of the state.56 The economic system and policies in France at that time shared significant similarities with contemporary Chinese capitalism: indicative planning through incentives, state ownership of the financial system and the largest industrial corporations, and a targeted industrialization policy supported by central bank monetary policies aimed at promoting growth. However, no one would have thought to attribute a “socialist” character to this policy in France. On the contrary, it was primarily pursued under the conservative presidents Charles de Gaulle and Georges Pompidou, and France was unquestionably regarded as a capitalist country and part of the anti-communist Western alliance system.

What are the reasons why state-owned enterprises can play an important role even in capitalist countries? In the monopolistic stage of capitalism, in most economic sectors – and in all medium- and high-technology industries – ultimately only monopolies are competitive, since only monopoly enterprises can raise sufficient financial resources to make the necessary investments. Moreover, transnational investment, that is, capital export, can generally only be carried out by monopoly corporations. Therefore, China’s rise to world power, particularly in the economic sphere, is only possible on the basis of a massive concentration and centralization of capital.

And this strategy is successful: while in 2000, only nine Chinese state-owned enterprises were among the 500 largest companies on the Fortune Global 500 list, by 2017 there were already 75.57 By 2023, the number of Chinese companies among the 500 largest had risen to 135.

The “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), the ambitious project to promote Chinese goods and capital exports, also primarily serves the monopolies or is implemented by them (see Chapter 5). It is therefore not surprising that the state is actively driving the centralization of capital: “To support the BRI and the ‘Going-out’ initiatives of state-owned enterprises, mergers to create large ‘national champions’ will help provide sufficient economic resources for mergers and acquisitions abroad as well as for research and development (R&D). The mergers will also help avoid the loss of financial resources due to price competition between state-owned enterprises in the international market.”58

In the 2010s, the SASAC implemented a targeted policy of creating large corporations through mergers among the largest state-owned enterprises under its supervision, and in the six years between 2012 and 2018 alone, it oversaw mergers involving 20 major state corporations.59

On the Character of State-Owned Enterprises in Contemporary China

Do the state-owned enterprises, which still account for a large share of China’s economic output, today represent a “socialist sector” within the Chinese economy? This is often claimed by propagandists of Chinese “socialism.” However, this is a fundamentally incorrect understanding of the role of these state-owned enterprises.

Fundamentally, it is crucial to note that socialism is not the same as state ownership of the means of production. Rather, socialism as a mode of production entails the elimination of capitalist laws and the organization of production according to the binding directives of central planning aimed at meeting societal needs. Naturally, this requires the nationalization of the means of production, but above all, it means that investment and production decisions of state enterprises are made in accordance with planning directives.

The character of an individual enterprise cannot be determined independently of the character of the economy as a whole and the economic laws prevailing within it: a state-owned enterprise in an economy functioning under capitalist laws and regulated by a bourgeois state cannot have a socialist character, because the state that owns the enterprises is a state of the bourgeoisie and accordingly uses state enterprises to secure the capitalist overall order and provide services for the accumulation of private capital. State ownership of the means of production is thus entirely compatible with a capitalist economy and, as has already been shown, is not unusual. For example, in Germany, Deutsche Bahn and the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau remain state-owned enterprises to this day.

Friedrich Engels already pointed this out: “The more productive forces it (i.e., the state) takes into its ownership, the more it becomes the real aggregate capitalist, the more it exploits its citizens.”60 And Lenin also stated: “In the era of finance capital, private and state monopolies intertwine, and both, in reality, are merely links in the chain of imperialist struggle between the largest monopolists for the division of the world.”61 The fact that an enterprise is state-owned, therefore, does not in itself allow any conclusions to be drawn about its social character.

The state-owned enterprises in China, in any case, have the typical form of capitalist state enterprises within a capitalist economy: as has already been shown, they serve the accumulation of capital in private hands. Moreover, they themselves are structured according to the same fundamental principles as private enterprises. It should be emphasized that in China, “political decision-makers as well as owners of state or collective enterprises can be understood in their economic behavior as analogous to private owners. What is decisive is not their legal status but their (economic) function.”62

The budgets of state-owned enterprises are formally and actually separated from the state budget under today’s Chinese corporate law. This has turned them into independent economic entities, whose activities are no longer directly controlled by the state and which no longer pay fixed contributions to the state but instead operate on their own account and are taxed by the state like any other enterprise.63 The “soft budget constraints” frequently criticized by liberal economists64 in socialist planned economies – meaning that a socialist enterprise would not simply go bankrupt in the event of financial losses but would be bailed out by the state – no longer exist in today’s China. The enterprises operate based on profitability criteria, and the state is often willing to let them fail in the event of losses.65 If a state-owned enterprise becomes insolvent, the question arises as to who bears the burden of the bankruptcy. In China, the practice has become established to prioritize the interests of the company’s creditors over those of the workers – debts to banks must be paid first, and only then are compensations for lost jobs considered.66

The industrial enterprises that were once fully controlled by the state were either fully privatized or partially privatized in the 1990s and 2000s. Even companies that are still officially classified as state-owned enterprises have sold a significant portion of their capital to private capitalists. By 2003, the share of stocks held by the state in state-owned enterprises averaged only 46.6%. By 2017, this had fallen to 38.3%.67 However, a state share below 50% does not necessarily mean that the state gives up its controlling influence over the enterprise: first, because the share of a company’s stock does not always correspond to the share of voting rights; second, because it is possible to maintain control through pyramid structures with less than 50% of the capital.68 Since the Chinese state explicitly aims to retain control over the state-owned economic sector, it can be assumed that these mechanisms are frequently employed. Moreover, the state appears to want to counteract the tendency for state revenues to erode gradually due to the ongoing partial privatization of state corporations. In 2015, it was decided to increase the share of profits that state-owned enterprises must pay to the state from 15% to 30%.69 Specifically, this means that state-owned enterprises must now transfer to the state a portion of their profits, which formally always belonged to the state but had previously been available to them for financing investments. Nevertheless, the trend described above clearly shows a continuous transfer of ownership of the means of production – and therefore also the claims to profit – from state to private hands.

Only a few large enterprises, primarily in the infrastructure sector, are still directly financed by the state in China. Most state-owned enterprises are listed on the stock exchange, like private companies, and are therefore directly subject to the pressure to distribute returns to shareholders.70 These state-owned enterprises, which represent the vast majority of Chinese state-owned enterprises, thus operate based on the criterion of profit and the unrestricted accumulation of capital. In 2017, Xi Jinping declared that 90% of state-owned corporations had already been restructured into joint-stock companies and that the remaining 10% would follow.71 As a result, the entire state-owned economic sector in China takes on the typical form of monopolistic finance capital, where an industrial corporation functions as a financial group and corporate financing is conducted through the equity participation system.

As a result of these reforms, the large state corporations have become largely autonomous enterprises. While their management remains accountable to state authorities, it faces almost no restrictions in its business decision-making. Financially, too, state corporations are independent capitalist enterprises. By the end of 2017, only 6% of the financial resources used by state-owned enterprises to finance investments came from the state.72